- Home

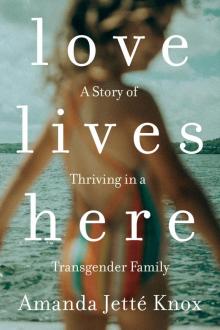

- Amanda Jette Knox

Love Lives Here Page 2

Love Lives Here Read online

Page 2

When that child was born, the doctors looked between the legs and declared it a boy. This is how things were done. Genitals = gender. Society wasn’t having meaningful conversations about gender identity—that was stisll decades away. But that little child, who everyone assumed was a boy, knew from an early age that “boy” didn’t fit.

This child was given a traditionally masculine name, but I won’t be sharing that here. In the transgender community, using someone’s old name is often referred to as “deadnaming.” It shouldn’t be done without permission because it can bring up a great deal of pain and put the person at risk. Yet despite the masculine name she was given and the gender marker stamped on her birth certificate, this child was always she. She was always she, even if the world perceived her as he and told her she belonged in that box, that category, that life.

But it should be noted that she was never a boy.

Peterborough, Ontario, served as the backdrop of her formative years. A mostly blue-collar, hockey-loving, factory-filled Canadian town of about sixty thousand people, it was not the place to declare a gender other than the one you were assigned at birth. But in all fairness, there wasn’t a place anywhere in the world at that time for a kid to make such a declaration. To do so would mean ridicule and perhaps even violence. To do so would mean conversion therapy—the standard medical treatment of the time, used to attempt to force that child into identifying as a boy.

And so, this child hid and pretended to be a boy, answering to that masculine name and playing the role of he and him.

She grew up shy and introverted, with few friends. Her biological mother, like my biological father, didn’t stick around. After divorce and a period of messy visitations, the mother packed up, left town and was never seen again. The girl from Peterborough and her younger brother were left in the care of a loving single father, who went on to marry a kind and compassionate woman who would fill the role of mother.

I often try to picture what it must have been like to be a male-presenting child who knew otherwise but had no one to confide in and no access to this gift of information we call the internet. I try to picture it, and I sometimes cry about it. I might not have had the easiest time in my formative years, but I never felt wrong in the body I was born in, or with the gender I was assigned because of it. That’s a deeper level of pain than I can imagine.

* * *

—

When I started kindergarten, I was one of the youngest in my class because my birthday fell on September 1. Being the class baby didn’t score me any points—nor did being one of the only English-speaking kids in a school full of francophones. We lived in Aylmer, Quebec, just across the border from Ottawa. It was the early eighties, and Quebec had spent several years seeking independence from Canada, fed by generations of ugly divide. We were just on the other side of the October Crisis and other terrorist attacks in the name of sovereignty, and tensions were still high.

In an attempt to ensure that Quebec retained its language and proud culture, the government introduced and strictly enforced Bill 101, the Charter of the French Language. Part of that charter deemed that if a child’s parents hadn’t been instructed predominantly in English when they were young, that child must attend a francophone school. And so, five-year-old me—a child who spoke very little French and was only nominally Catholic—was put into a French-Catholic school a few blocks from our home.

It’s a challenge to turn on the charm in a language you don’t understand, and I was left awkwardly trying to comprehend what everyone was saying. There was no way to show the other kids that I was sunny and funny. There would be no external validation to feed my sense of belonging. I had entered new and uncomfortable territory.

Typically, little cliques formed in the class and spilled into the schoolyard. I was desperately trying to figure out where I fit in when I found a small cluster of English kids who looked just as terrified as I was. We played together out of necessity. Even the francophone children who didn’t ignore us weren’t exactly kind to us. Despite the language barrier, we could see we were disliked. Getting yelled at or shoved was a solid indicator. Being called a “maudite Anglo”—a damn Anglo—was another. Looking back, I’m guessing some of these kids were going home to families determined to see Quebec become its own country, and they were probably overhearing conversations at the dinner table about how English-speaking Canada was to blame for many of their problems. They would then bring this sentiment to school with them, and we maudites Anglos felt it.

While some of the Anglo kids found their way into other circles over the next few months as they picked up more French, the rest of us never really became a part of the social fabric, no matter how hard we tried. I was one of them. To this day, my mom says I was simply “too nice,” and that it’s often the nicest people who become the biggest targets. It’s true that I tried hard to be kind to those who were cruel, and never fought back when I was mocked or pushed around. Add in the language barriers, and it created a volatile mix of failed people-pleasing and insecurity.

This exclusion caused another crack in my foundation—another reminder that I was less sunny, less funny and less lovable than I thought.

* * *

—

In Peterborough, the girl who wasn’t seen as one made her way to the library.

She was looking for answers to questions she had kept secret for a very long time. If she was a girl in the way she thought and felt, why didn’t she look like one? Why did she have the body she had—the one she was told belonged to a boy? Why wasn’t she developing the way the other girls her age were, with a hint of hips and breasts and a softness to her face? Why, instead, was her body changing in ways that felt completely alien? These thoughts were weighing heavily on her mind. But she didn’t have anyone to talk to about them. Who would understand? So she turned to whatever reading materials she could dig up.

As she steered her way toward the children’s section in the brown brick building on Aylmer Street, her long, graceful fingers ran across book spines and flipped through pages. After an exhaustive but unproductive search, she moved into adult nonfiction, poring over books on anatomy and puberty, looking for a medical explanation of what was happening inside her. But she found nothing about experiences like hers—only chapters full of shoulds.

Females in this age group should look like this.

They should see these changes.

They should feel this way.

The books told her she should, but she didn’t and she couldn’t, no matter how hard she tried. Her body, filled with an abundance of the wrong hormones, was transforming her into what society defined as a pubescent boy.

The only place she found mention of experiences like hers was inside a couple of psychiatry books. What she was going through was a fetish, these books explained. It was sexual, deviant and a sign of mental illness. There was something terribly wrong with her. Mortified, she pushed these books aside. Was this who she was? Was she sick? Shame wormed its way into every part of her. She could see no way out, no way to right this wrong. Research had failed her, and she found herself feeling more alone than ever.

Utterly defeated and on the verge of tears, she grabbed her bike and pedalled down the street as fast as she could, hoping to outrun the girl inside of her.

* * *

—

I did have one good playground friend in my elementary school years. Jasmine and I spent recesses trading stickers, playing marbles and talking about all the things we were going to do together in high school and beyond. She didn’t mind how much I loved books and overlooked my awkward Anne of Green Gables phase (braids and all!). I lived in my head much of the time, and she indulged me in my endless imaginary play.

In the years Jasmine and I weren’t in the same class—by far the worst years for me—I would stand outside at recess and wait for her to join me. Groups of kids would run by, name-calling, but they didn’t bother me nearly as much as the two girls who liked to approach me directly.

They would find wherever I was waiting, a lone target to prey on.

“What are you doing?” the more forceful one would ask.

“Waiting for my friend,” I’d reply in my best French, trying not to make eye contact. “She’ll be here any minute.”

“What’s that?” the sidekick would ask, looking at whatever I had in my hands.

Damn it. I knew this dance.

My dad liked to buy me things he knew I’d find special. When I fell in love with the movie E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, he bought packs of trading cards to surprise me. He would take me out every Friday so I could pick out a Smurf figurine or some cards of the Garbage Pail Kids, a gross parody of Cabbage Patch Kids that was all the rage for a while. I doubt my dad understood my love of them, but he did love seeing me smile when we went to the dépanneur to get them.

“Nice card,” one of the girls would say. “I don’t have that one yet. Can I see it?”

“No, I don’t think so,” I’d reply, a part of me hoping it was merely a polite request.

Sometimes they would persuade me with verbal threats, and sometimes one of them would simply hold me while the other wrenched the card or toy out of my hand. I would kick myself for bringing something I cherished to school and go home that day not only ashamed but also guilt-ridden because I’d lost something my dad gave me. I had been so careless with a manifestation of his love, and I worried that he would find out and be hurt. Or even worse, that he would be angry and not want to love me anymore. Just like the man who was supposed to but didn’t.

I never fought back against the kids who hurt me. I didn’t retaliate against the ones who threw me in a snowbank at every opportunity, holding me face down while I gasped for air. When a girl who had taunted me for months hit me in the face with her metal lunch box one day, bruising my cheek and giving me a black eye, I didn’t hit her back. I don’t know if it’s because part of me believed I deserved it, or if I was simply too scared to stand up against the aggressors. Maybe it was a bit of both. Each time I was bullied in any fashion, I would turn the anger inward. I would berate myself for bringing that special thing to school. I would shame myself for being a target. I would blame myself for not being enough. I would internalize their words, stashing them in a corner of my brain to take out later and replay over and over.

You are worthless. You are meaningless. You are different. You are not enough.

Never enough.

Jasmine’s friendship made school bearable. At times, she was my only reason to get up and face another day. But by grade four, she had come to realize that our friendship might be more of a liability to her than an asset.

“You know,” she said aloud to me one sunny day, as we stood by a fence overlooking an open field of tall grass, “maybe if I stopped hanging around with you, I could make more friends.”

She didn’t say it maliciously. She was thinking aloud, as kids often do when they come to a realization. It was honest and painful to hear.

Also, she was probably right.

Over the years, groups of girls had swooped in to try to collect Jasmine, to bring her into their circle. And why not? She was smart, pretty and had plenty of personality. She likely would have been at the top of the social ladder if her mother hadn’t worked for the school board. Some kids were willing to overlook that, but they wouldn’t overlook me. And since we were a package deal, those offers to join their fun would always fizzle out quickly. Then it would be just the two of us again.

That day, when Jasmine expressed her desire to branch out, my heart sank and I had to focus extra hard on the tall grass swaying in the breeze to stop myself from crying. I didn’t look at her when I replied.

“Yeah, maybe. I guess,” I said, flustered. “But I thought we were friends.”

The bell rang, and I was able to spare myself her reply. That was enough honesty for one recess.

I felt sick for the rest of the afternoon. I was in panic mode, desperately trying to come up with a way to keep my only friend. The crack in my foundation grew wider, deeper and more painful. Someone else I loved was going to leave because I wasn’t enough, and there wasn’t a damn thing I could do about it.

Or maybe there was. An idea was forming.

* * *

—

Two years earlier, when I was seven, my parents had sat me down to tell me about my biological father. I was getting older and starting to ask questions about why my last name was different from theirs.

I remember sitting on the kitchen stool, listening to my parents try to explain the unexplainable. My swinging legs stopped dead as my father said, “I’m not the dad who was with you the day you were born—that was another man. Yes, he knows about you. No, he isn’t around. No, we don’t know why. No, we don’t know where he is. We wish we had those answers, sweetie. But I love you and I am your dad.”

My head swam with this new information. The man I thought was my father—the man who had been in my life for as long as I could remember—was telling me he only took on the position after someone else resigned.

Hats off to my parents. They tried very hard to persuade me that my biological father’s departure had nothing to do with me. They reminded me how loved I was and how special I was, and they explained that grown-ups sometimes make decisions that are hard to understand. They said that I was still their beautiful girl, and that Charlie would always be my dad. Dads, after all, are the men who take on the role.

I wish I could have believed them.

That first crack in my foundation is still the biggest. To this day, abandonment hurts me like little else can. The fear of being left behind began in that moment, on that stool in the kitchen. Because if he could leave, anyone could.

My parents could.

Jasmine could.

Which is probably why, when I heard Jasmine’s musings two years later, I came home from school with my heart pounding and my pulse racing. I ran for my art supplies. I spent an inordinate amount of time crafting her a card filled with pictures and sentiments about how special she was to me. It was colourful and happy. I taped whatever coins I could find to the inside and wrote the words “Please still be my friend” beneath them.

The next morning, I presented her with the card and anxiously awaited her response. I needed her not to leave me all alone in that miserable schoolyard. She mulled it over for most of the day, and ultimately decided we could stay friends. At least in the short term. But she didn’t rule out setting off on her own in the future.

That was the first of a handful of times I made a card like that and held it out for Jasmine to read, my stomach in knots. Yes, you read that right: I literally paid someone to be my friend. I was willing to do anything at all to keep the pain away, including reducing myself to a few coins and the promise to try to be a better friend to someone who, frankly, didn’t deserve that friendship.

THREE

self-destruction

THREE HOURS AWAY, the girl in Peterborough was struggling to get through school. She was smart, studious and talented. She was driven, capable and organized. Thanks to her naturally inquisitive mind, she was a teacher’s dream, learning with ease and excelling at anything she took an interest in. There was just one problem: she didn’t excel at playing the role of a guy. She looked like one—with her short black hair and enviable height—but an innate femininity lived inside her and emanated outward, no matter how hard she tried to hide it. She had been teased for this for as long as she could remember.

“You’re a fag!” the boys would yell, hitting the girl they thought was a boy. They followed her around, doing their best to make her life miserable. They stole her bike and kicked her as she lay on the ground, trying not to cry. Every day was a nightmare.

The confused and hurting girl who could find no others like her—no examples of girls who had to pretend to be boys—was hurting deeply. She had no answers to why she felt as she did, and no safe person to confide in. She thought about telling her parents who she really was, but how c

ould she even begin that conversation? And what could they do to help her, even if they believed her?

Things got so bad that she had to switch high schools. The school board had been sending her to class in a taxi every day because she was harassed on the bus. At her new school, she learned to keep her head down and focus on her studies. As she grew older, she became more adept at hiding who she was. The girl worked harder at playing the role of he and him. She studied masculinity and tried her best to model it. But this inauthenticity came at a cost. The softness within her grew hard; the sweetness grew sour. Eventually, hurt and fear boiled down into anger and festered inside her. She was sullen one moment, full of rage the next. Her heart was at war with her brain.

Her parents didn’t know what to do to help this girl they thought of as the elder of two sons. Her anger was bordering on dangerous, her grades were slipping and her life was falling apart. They had her speak with doctors and psychologists, but no one could get to the root of the problem because she dared not say what it was.

By sixteen, she was living on the streets of Toronto, charging headlong into a self-destructive spiral.

* * *

—

Meanwhile, a perfect storm was brewing in my own life.

I’d started grade seven at a large francophone secondary school. There were no middle schools in the French system at the time—no hormonal thirteen- and fourteen-year-olds smushed together into our own building until we maxed out our growth spurts. Nope, we were playing in the big leagues, walking among giants, from the very first pimple.

Thankfully, I fell into a small but welcoming group of girls that included my childhood friend, Emmy. Her grandparents lived in my neighbourhood. We didn’t attend the same elementary school, but we spent our weekends and summers together. Emmy introduced me to her friends, and because they had no idea about my social-pariah past, I hoped this would be my fresh start. Despite my best efforts to reinvent myself in this new space, however, my reputation as an awkward social pushover soon became known. Melanie and Sylvia, inseparable friends who were definitely not my friends—once they had chased me down the road, trying to throw lit matches in my hair while laughing hysterically—were forging connections in our new school, and they introduced me as a target to a whole new group of people.

Love Lives Here

Love Lives Here